Many well meaning Americans trying to follow foreign policy are treated to a disjointed, confusing narrative that jumps from one flashpoint to another. Every few weeks a new crisis dominates the news, the reporting adds little to our understanding of the way the world works, and the resulting debate is shallow and familiar.

Current news about Syria is the most recent example. There are important questions that a sincere observer might ask about the situation, not only to better understand it, but to advocate for a particular course of action (or inaction) that is consistent with their values.

For example, how does the use of chemical weapons fit into the framework of international law, and why is the United States proposing military action rather than a legal investigation that might hold the perpetrators accountable? After all, when a violent, calculated crime is committed in our local community we understand that society is better served by an investigation, trial, and the meting out of appropriate justice. Why, in the United States, do we spend so little time thinking about how this international framework is supposed to work?

The United States and Chemical Weapons

The use of chemical weapons has long been a broadly agreed upon violation of international law, established in the 1925 Geneva Protocol, and most currently, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which went into effect in 1997. These international accords call on all signatories to declare their stockpiles of chemical weapons and, over time, destroy them. Syria (along with Israel, North Korea, Myanmar, Angola, Egypt, and South Sudan) has not ratified the CWC. This fact, however, does not prevent other nations from bringing charges against Syria for a crime against humanity in the United Nations General Assembly and Security Council. Both the United States and Russia have declared stockpiles of chemical weapons. Both countries have missed their agreed upon deadlines to destroy those weapons.

As the Obama administration proposes unilateral military action against Syria, illegal because it would be a use of force not approved by the UN Security Council under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, and argues that this action is justified by Syria’s alleged chemical weapons use, the logical response is to look at the recent history of the U.S. and its relationship to chemical weapons use. We ought to understand that, on any scale from local to international, (1) conducting vigilante acts outside of a legal framework is dangerous because it sets a precedent for others to do the same, and (2) the vigilante’s motives ought to be examined.

A recent story in Mother Jones, “Are Chemical Weapons Reason Enough to Go to War?”, poses the question of how the United States has reacted to chemical weapons use in the recent past. Daryl Kimball, the executive director of the Arms Control Association, is asked if the U.S. push to bomb Syria in retaliation for alleged chemical weapons use is the historical norm. He answers: “As far as I know this would be among the first instances when a state’s use of chemical weapons would have prompted military action by the U.S. or by others.”

Even worse than inaction, the record is one of occasional U.S. complicity in chemical weapons use. A recent article in Foreign Policy magazine, “Exclusive: CIA Files Prove America Helped Saddam as He Gassed Iran” describes  intelligence documents that show the United States provided tactical help to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq with full knowledge that he would use it to launch chemical weapons attacks, using the nerve agents sarin and mustard gas, against Iranian soldiers in 1988. These same chemical weapons were used that year against Kurdish villages in Iraq, during a period when U.S. intelligence was flowing freely to Saddam Hussein’s military. Ironically, this crime against humanity would later become part of the rhetorical case for launching the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq.

intelligence documents that show the United States provided tactical help to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq with full knowledge that he would use it to launch chemical weapons attacks, using the nerve agents sarin and mustard gas, against Iranian soldiers in 1988. These same chemical weapons were used that year against Kurdish villages in Iraq, during a period when U.S. intelligence was flowing freely to Saddam Hussein’s military. Ironically, this crime against humanity would later become part of the rhetorical case for launching the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq.

More recently the United States has used white phosphorus in the town of Fallujah during the war against Iraq. Nominally, white phosphorous is intended to illuminate a battlefield at night or to generate smoke to obscure the movement of troops. In practice, when used in urban areas, the effect is much like the napalm that the U.S. used in Vietnam – the hot substance sticks to the victim’s skin, burning all the way to the bone as it releases a toxic phosphorous acid into the flesh.

Initially the U.S. denied using white phosphorous in Fallujah. When the admission finally came officials immediately turned to arguing that white phosphorous is not technically a chemical weapon (as did Israel, after admitting to use of white phosphorus during its Cast Lead operation in the Gaza Strip). A representative of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which oversees the Chemical Weapons Convention, responds to that argument with this: “If … the toxic properties of white phosphorus, the caustic properties, are specifically intended to be used as a weapon, that of course is prohibited, because the way the Convention is structured or the way it is in fact applied, any chemicals used against humans or animals that cause harm or death through the toxic properties of the chemical are considered chemical weapons.”

(as did Israel, after admitting to use of white phosphorus during its Cast Lead operation in the Gaza Strip). A representative of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, which oversees the Chemical Weapons Convention, responds to that argument with this: “If … the toxic properties of white phosphorus, the caustic properties, are specifically intended to be used as a weapon, that of course is prohibited, because the way the Convention is structured or the way it is in fact applied, any chemicals used against humans or animals that cause harm or death through the toxic properties of the chemical are considered chemical weapons.”

The United States and International Law

When we consider the U.S. record on chemical weapons use, both directly and indirectly, it becomes clear why the United States is quick to dismiss international law as a framework for delivering justice. An appeal to international law legitimizes the notion of a functioning international legal framework, where the weak could seek justice against the powerful. Powerful nations like the United States (and Russia, China, etc.) are careful to resort to such an argument given that a functioning system could (1) hold them accountable for abuses and (2) remove the opportunity for the occasional military action masquerading as humanitarian intervention.

A reasonable response to this critique — one made by many Democratic defenders of Obama — might be: “If the U.S. tried to pursue the proper legal course for the victims in Syria a UN Security Council resolution would be vetoed by Russia. Maybe, imperfect as it is, the Obama administration might use airstrikes to prevent future loss of life and the use of chemical weapons will be punished.”

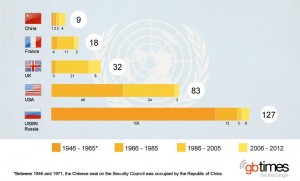

Truly, Russia almost certainly would veto a UN Security Council resolution, making any military action not taken in self-defense illegal (again, Chapter 7 of the UN Charter). Like the U.S., Russia has used  chemical weapons in the past (for example, against protestors in Tbilisi, Georgia in 1989), and more importantly they are allied with the Syrian regime and would not like to see it weakened. It is an anti-democratic feature of international law that the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (U.S., U.K., France, China, and Russia) have veto power over any resolution with binding force (a power used far more by the U.S. than any other permanent member, from 1966 to today – click image to left to enlarge, follow this link for an interesting list of all UN Security Council vetoes). This framework, a legacy of the UN’s founding immediately after World War II, screams for reform. But meanwhile, does it follow from this that the U.S. should carry out military strikes, with or without allied nations?

chemical weapons in the past (for example, against protestors in Tbilisi, Georgia in 1989), and more importantly they are allied with the Syrian regime and would not like to see it weakened. It is an anti-democratic feature of international law that the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (U.S., U.K., France, China, and Russia) have veto power over any resolution with binding force (a power used far more by the U.S. than any other permanent member, from 1966 to today – click image to left to enlarge, follow this link for an interesting list of all UN Security Council vetoes). This framework, a legacy of the UN’s founding immediately after World War II, screams for reform. But meanwhile, does it follow from this that the U.S. should carry out military strikes, with or without allied nations?

The Question of Harm

Veteran reporters in the region are almost unanimous in warning that any bombing campaign will intensify the violence and do nothing to hold parties accountable for violating the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Longtime Middle East reporter Patrick Cockburn argues for mediated talks, starting immediately: “the sense of urgency among foreign powers generated by the present crisis should be used to launch the much-delayed peace negotiations in Geneva.”

Even more alarming, Cockburn reports that right now the U.S. backed rebels, who would benefit from an American airstrike, “have been carrying out a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Syrian Kurds in the north-east of  the country, forcing 40,000 of them to flee across the Tigris into northern Iraq in less than a week. So many are trying to escape in what the United Nations says is the biggest single refugee exodus of the war that the pontoon bridge across the Tigris they were using is near collapse and has had to be closed, trapping tens of thousands of terrified Kurds inside Syria.”

the country, forcing 40,000 of them to flee across the Tigris into northern Iraq in less than a week. So many are trying to escape in what the United Nations says is the biggest single refugee exodus of the war that the pontoon bridge across the Tigris they were using is near collapse and has had to be closed, trapping tens of thousands of terrified Kurds inside Syria.”

When our focus is limited to the narrow scope of the latest crisis in the headlines, we accept narrow debates over false choices. But if we ask better questions we can find the opportunity to broaden the dialogue with others and in the process deepen our understanding of the world.

When we question the U.S. push for air strikes cloaked in humanitarian rhetoric we should be asking logical questions about the strategic goals in the region, and whose interests these goals serve. These questions ought to shape the way we talk about foreign policy with friends, co-workers, etc. We’re all subject to the same stifling news media and it’s not worth much to overcome that in isolation.

In the current case, rather than be drawn into an absurd debate about bombing Syria to promote justice and democracy, we might test the whole premise that policy makers are seeking to promote democracy and justice in the region. To do that we should look to the human rights records of the countries that are allied with the U.S. and directly benefit from military, financial and diplomatic support.

Looking to the prime U.S. allies the picture is not good:

— Bahrain’s monarch met non-violent democracy protestors with violence, detention, and torture and U.S. support of has continued. Bahrain is the home of the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet (2013 Amnesty International report on Bahrain).

— Saudi Arabia, an undemocratic, repressive monarchy, is among the closest U.S. allies in the region and has effectively repressed dissent from repressed classes, including women (2013 Amnesty International report on Saudi Arabia).

— Egypt’s military still receives $1.3 billion per year from the U.S. (which it then spends on American weapons) even after a violent massacre of protestors following a military coup.

The list continues (Israel, Kuwait, Turkey) and, interestingly, the Obama administration has a promising pathway to support democracy and champion human rights – by ending its support for repressive regimes. This is something that we can advocate for no matter what the news of the day is.